How Whole Systems Thinking Could Transform the Pharmaceutical Value Chain

What's this about?

Stakeholders in the pharmaceutical industry are increasingly demanding radical improvements in performance in terms of affordability, safety, efficacy and quality of medicines produced. This paper asserts that no matter how much stakeholders battle against the system, the fundamental modus operandi of the industry is not fit for purpose and requires radical reform.

This is not a new call for action, of course; many are making the case, including high-profile politicians, but little seems to be making a difference.

Here, we take a deep dive into the systemic aspects of the medicines discovery and development process, to learn that major strategic errors have been made over the last forty plus years, resulting in value chains that are overly complex, cost burdened, and patient agnostic.

We therefore turn to whole systems thinking and the people-purpose system, to deliver what we believe is a feasible solution. This involves intense focus of on end-users of medicine, tight integration in the development process and keen awareness of the value proposition to be delivered; the result being safe, better, cheaper medicines fit for the 21st century.

Is the system broken?

Medicines are a major intervention in healthcare. As such, they play a crucially important role in the health and wellbeing of patients around the globe, as do the companies developing and supplying them - pharmaceutical companies.

There have been important breakthroughs in medicines over the years, such as penicillin, the polio vaccine, synthetic insulin, treatments for cancer, HIV/AIDS and Hepatitis C, to list some examples.

Notwithstanding these important breakthroughs, the development of the medicines value chain has fallen well short of other more progressive industry sectors, such as the semiconductor, aerospace, electronics and automotive sectors. Those sectors have leveraged innovative approaches such as design for manufacture (DfM), quality systems meeting six-sigma performance levels (3.4 defects per million opportunities) and voice of the customer (VoC) to inform their understanding of the end-user value proposition.

In the case of Pharma, it is generally accepted that quality levels attained are in the range 2.5 – 3 sigma (70,000 – 100,000 defects per million opportunities). On hand inventory levels are measured in months, not weeks or days, and it is not uncommon for delivery lead-times be up to six months.

While operational performance has been a major concern, in latter years, EU and US Governments and have had to step in with legislation aimed at correcting potentially life-threatening issues of economically motivated adulteration, counterfeiting, theft and cargo diversion. In the EU, the Falsified Medicines Directive (FMD) has taken nearly nine years to implement and it still does not solve the issue of adulteration taking place prior to the finished product manufacture. The picture for the US’ Drug Supply Chain Security Act (DSCSA) is similar.

This article therefore concludes that the system giving rise to the pharma value chain is well and truly broken.

How did the system get broken?

In 1976, Smith, Kline & French (SK&F) launched Tagamet, an anti-ulcer treatment.

Five years after Tagamet’s launch, Glaxo’s competitive product, Zantac, was approved and was outselling Tagamet 3:1 within a few years, based on superior sales & marketing activity. In response to the massive profits for both companies, Pharma companies changed strategy to focus on discovery of patented new molecular entities (NMEs) and sales & marketing. Product development, manufacturing and supporting activities were outsourced.

We see below this represented diagrammatically. A patented molecular structure (compound), with an approval to sell from the regulator, leaves a monopoly or oligopoly position which can be leveraged to exploit the market over the remaining patent life.

What was the impact on the value chain?

Displaced executives set up small companies (termed small drug developers – SDDs - here) undertaking early stage development to either sell to Big Pharma or try to get to market themselves. The CEOs of SDDs were making a persuasive case to be the engine house of drug discovery, citing less bureaucracy and shorter chains of command. Venture capital investors liked the sound of it, and started funnelling funds in.

Other exiting executives joined together, bought up the facilities, employed the people, and set up companies known as contract development and manufacturing organisations (CDMOs) and contract research organisations (CROs). These companies provided Big pharma and SDDs with services in exchange for a fee, under contract.

Handling customer complaints and dealing with ever more frequent deliveries were not deemed core and Big Pharma handed over all its warehousing and distribution assets to the wholesaler network. Similarly, specialist third party logistics providers (3PLs) grew their businesses as supply chains expanded in length and complexity.

The final arm of the strategy was the practice of exiting existing product markets once the patent expired, as they didn't meet the ROI targets the branded versions had enjoyed.

Enter companies with more modest profit aspirations working to much tighter margins, copying the originals. This gave rise to the generics industry.

In summary, pre-blockbuster era pharma companies were mainly vertically integrated, as shown in Figure 1 below:

Figure 1: The Value Chain Before the Blockbuster Era

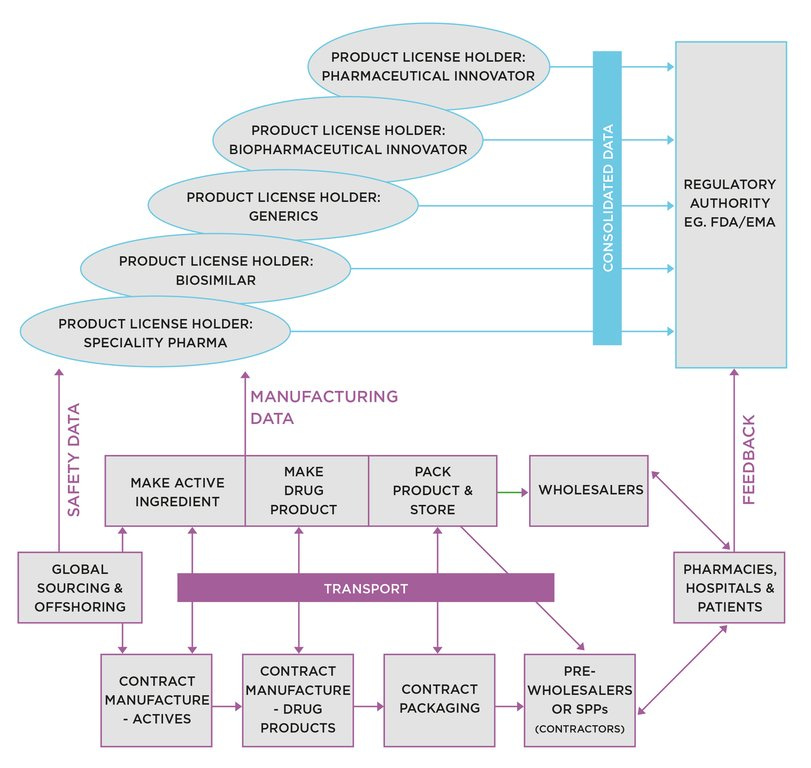

Post blockbuster era, we have an arrangement shown in Figure 2:

Figure 2: The Value Chain post Blockbuster Era

We identify the contributory factors leading to this degree of complexity:

Outsourcing drug development, manufacturing and distribution activities.

Sourcing input materials from low cost countries.

Outsourcing early stage development programmes to SDDs, creating their own less robust supply chains.

Discontinuing products when out of patent, resulting in new supply chain entrants from the generics sector greatly increasing complexity.

How can whole systems thinking reverse this?

Complex theories abound in the realms of whole systems thinking, and the areas in which it can be applied. The treatment here limits the analysis to what, in more recent times, are referred to as ‘socio-technical systems’. In simple terms, this is the combination of people, resources and technology working in concert to achieve defined ends. For our case here, the defined end is the delivery of fit-for-purpose products to end-users.

I coined my own term for these systems in Taming the Big Pharma Monster by Speaking Truth to Power, namely people-purpose systems (PPS) As we look at the elements of a strong PPS below, it will become clear how the present-day pharma value chain has underperformed.

For more on this topic, please check out: Taming the Big Pharma Monster by Speaking Truth to Power, and/or

What Patients Need to Know About: Pharmaceutical Supply Chains

If you want up-to-the minute news from Inside Pharma, subscribe to